Wasteland, Baby!

by Laura Frölich (M.A. student of Theatre Studies)

Hello there. My name is Laura Frölich and I am studying theatre studies at Ruhr University Bochum, so my interest in theatrical projects is pretty obvious. Two years ago, I was already part of the Play/With/Brexit theatre project led by Anette Pankratz, Niklas Füllner and Kai Bernhardt, in which Mr. Shakespeare himself played a part.

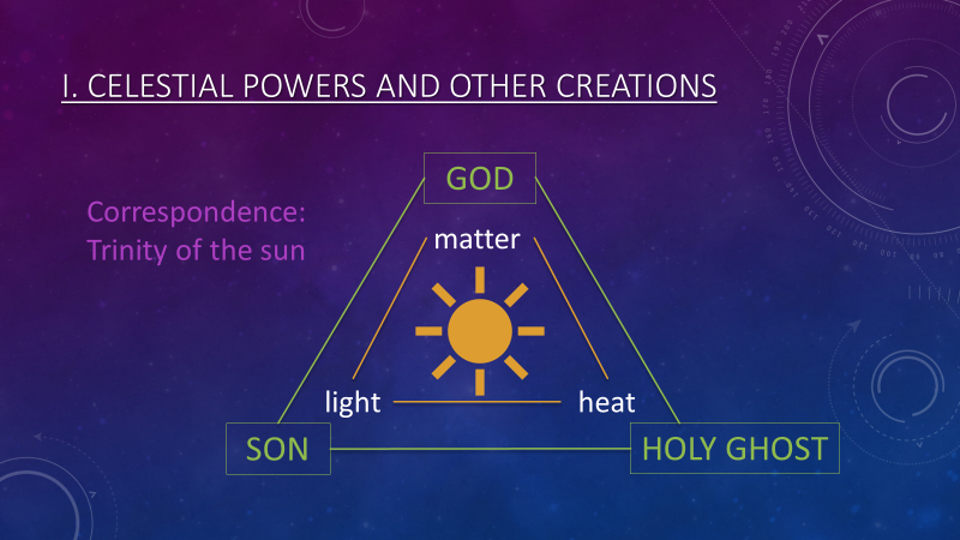

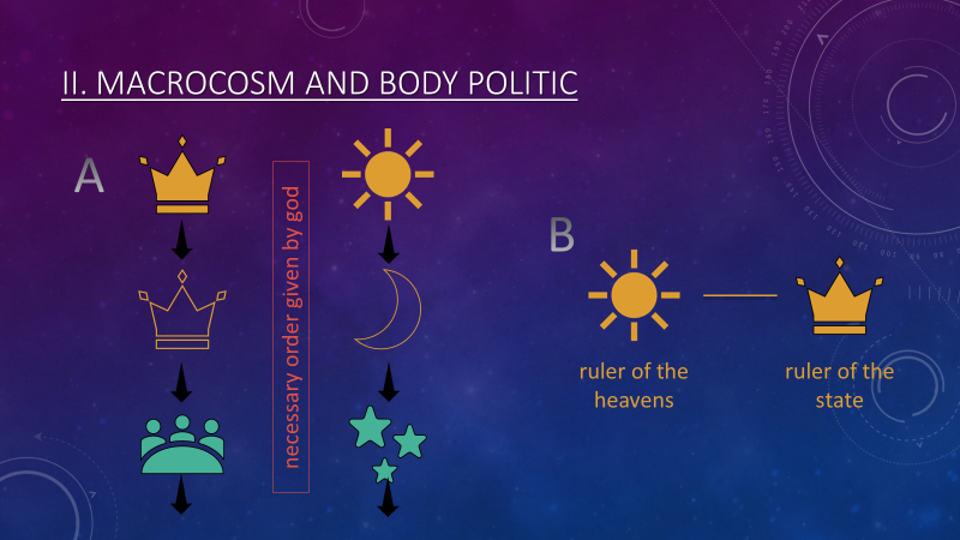

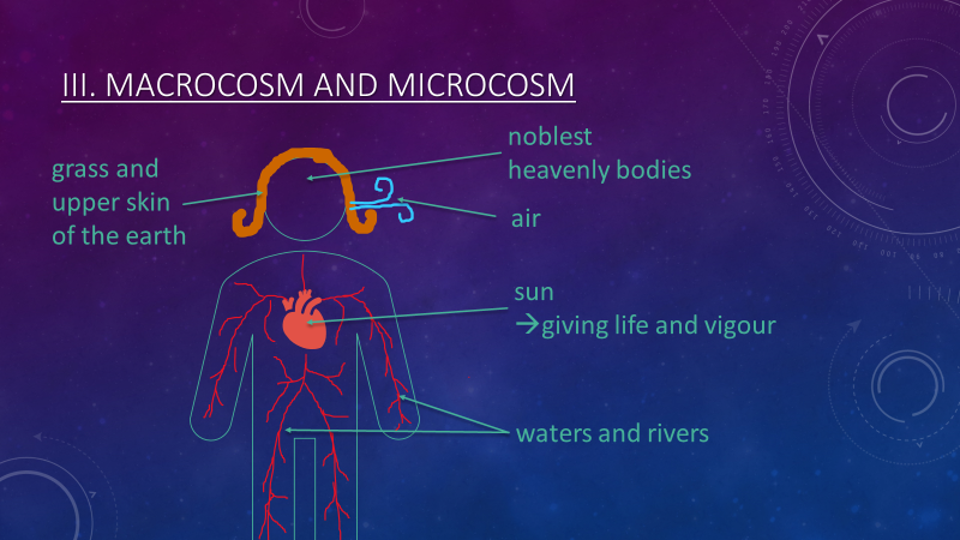

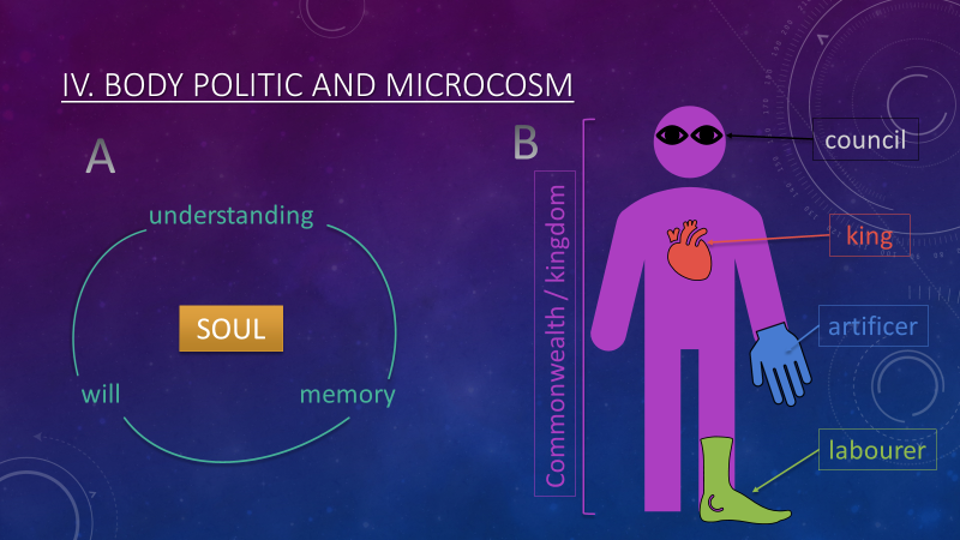

In the seminar of this module my friend and fellow student Anthea and I gave a presentation on Elizabethan notions of order and disorder. As I am a huge fan of Greek, Roman and Norse mythology, I found this topic particularly interesting. Although these are outdated ideas, I am fascinated by the way people back then tried to explain and understand the world and (cosmic) phenomena. In mythology these phenomena are personified. The so-called "Elizabethan World Picture" worked in a slightly different way but is no less interesting. In the geocentric cosmos everything is arranged in a hierarchical order. God is at the top of creation, the sun is the highest ranking 'planet', the monarch represents the top of society, the eagle is the king of animals and the father and husband is head of the family, and so on. The correspondences between the hierarchies in the different spheres of the universe are the second ordering principle in this cosmology. For example, the 'natural hierarchy' in the macrocosm can be also found in the body politic. The analogy even extends to the body, the microcosm of 'man'. For example, the veins carrying blood can be compared to rivers carrying water, and the hair covering our body corresponds to the the grass covering the earth, and so on. As mentioned before, these concepts of nature and the cosmic order are outdated and science has proven them wrong (with only a few esoteric minds still believing in them). But the idea that in nature everything is connected with each other and that interfering with this order has drastic consequences for the entire ecological system is a notion not so alien to us.

In theatre studies we have a seminar series called "New Mythology", where we examine Romantic literature and how it uses motives from ancient tales and myths which had been discarded in the previous era of enlightenment. To compensate for the lost sense of community brought about by the end of tales and myths in the 'Age of Reason', Romanticism fostered and satisfied the need for new tales and myths. This interest has lasted until today, as can be seen by the great popularity of fantasy literature and movies. They show us new worlds, fictional folklores, fictional history and new myths which are based on ancient myths but still innovative enough to fascinate new generations. Tolkien's Middle Earth stories are a good example.

To sum up: Mythology is great and (sometimes) pretty underrated in our modern times. I am not suggesting that we should believe in it. But myths and concepts such as the Elizabethan World Picture can inspire us to think about the world in a more holistic way. For our presentation in the seminar I created pictograms to illustrate some of the main structuring principles of the Elizabethan World Picture. I have included them here in the hope of making some of the ideas clearer and (hopefully) arousing your interest.

In the seminar of this module my friend and fellow student Anthea and I gave a presentation on Elizabethan notions of order and disorder. As I am a huge fan of Greek, Roman and Norse mythology, I found this topic particularly interesting. Although these are outdated ideas, I am fascinated by the way people back then tried to explain and understand the world and (cosmic) phenomena. In mythology these phenomena are personified. The so-called "Elizabethan World Picture" worked in a slightly different way but is no less interesting. In the geocentric cosmos everything is arranged in a hierarchical order. God is at the top of creation, the sun is the highest ranking 'planet', the monarch represents the top of society, the eagle is the king of animals and the father and husband is head of the family, and so on. The correspondences between the hierarchies in the different spheres of the universe are the second ordering principle in this cosmology. For example, the 'natural hierarchy' in the macrocosm can be also found in the body politic. The analogy even extends to the body, the microcosm of 'man'. For example, the veins carrying blood can be compared to rivers carrying water, and the hair covering our body corresponds to the the grass covering the earth, and so on. As mentioned before, these concepts of nature and the cosmic order are outdated and science has proven them wrong (with only a few esoteric minds still believing in them). But the idea that in nature everything is connected with each other and that interfering with this order has drastic consequences for the entire ecological system is a notion not so alien to us.

In theatre studies we have a seminar series called "New Mythology", where we examine Romantic literature and how it uses motives from ancient tales and myths which had been discarded in the previous era of enlightenment. To compensate for the lost sense of community brought about by the end of tales and myths in the 'Age of Reason', Romanticism fostered and satisfied the need for new tales and myths. This interest has lasted until today, as can be seen by the great popularity of fantasy literature and movies. They show us new worlds, fictional folklores, fictional history and new myths which are based on ancient myths but still innovative enough to fascinate new generations. Tolkien's Middle Earth stories are a good example.

To sum up: Mythology is great and (sometimes) pretty underrated in our modern times. I am not suggesting that we should believe in it. But myths and concepts such as the Elizabethan World Picture can inspire us to think about the world in a more holistic way. For our presentation in the seminar I created pictograms to illustrate some of the main structuring principles of the Elizabethan World Picture. I have included them here in the hope of making some of the ideas clearer and (hopefully) arousing your interest.

Wasteland, Baby!

by Kim Migowski

Somehow, it is only when it is too late for change when we take action. We see it with the late responses in this pandemic, see it with environmental issues and with many other systemic problems we encounter day by day. Only when the repercussions of our actions become tangible, we try our utmost to reverse the damage, searching for some wondrous solution or hoping for someone to solve it. This is not the place to get pessimistic, and I certainly don’t want to. However, it is one of the themes we thought of when working on our project

Wasteland, Baby!

Here, the repercussions of deforestation become only tangible when Shakespeare's Malcolm realizes he cannot invade Dunsinane without the help of Birnam Wood.

Not Shakespeare, though, but Christopher Marlowe, who has been given the task and responsibility to handle the situation against his will, has to try to work it out. One man to figure out the problems of everyone else, which ultimately are also his own. But there are some things we just cannot do on our own. Some things are too big and require too much effort to try to achieve on your own. We cannot fix everyone's problems, and we certainly cannot regrow a forest all on our own. A communal problem needs a community to solve it. Therefore, Marlowe tries to go for the easy solution and get help. In order to regrow trees, he turns to a higher being, Oberon, to have them magically regrown. However, the magic is gone. Deforestation has drained the fairy king of his once held powers.

This seminar made it all the more clearer to me, how impossible it is to work alone. A theatre production requires a team for a reason. There are too many tasks, too many required skills, and too many things to keep track of, making it impossible for one person to handle everything on their own. And this seminar was no different. In trying to work through a complex topic like ecocriticism in the Early Modern Age in only three days, we split up into groups, each to work on a presentation and hosting a session on one particular enviromental issue. Similarly, when working on the individual performance projects, we split into groups once more to create parts which would then be assembled into a large project.

At first I was intrigued by the seminar and the mystery of how the two – in my opinion separate – fields of study, early modern literature and ecocriticism could be studied together. I was unaware of the environmental concerns in the period and how important they were for the culture of the time. Secondly, since a lot of friends took part in the course as well, and as I have a practical interest in theatre, it was clear to me that I had to take part. I was interested and enthusiastic about getting onto a stage with a group of nice people and performing something again after such a long time, deprived of any form of theatre experience due to the pandemic. I was optimistic, like probably many, that we would be able to actually perform in a theatre in front of an, albeit smaller, audience.

However, given the circumstances, we had to change our ideas and how we would meet in the seminar. And we did that together. We came up with possible solutions on how to carry out the theatre laboratory and how to make online performances possible. We discussed, imagined and worked together to create a performance we might not have imagined, but which we hopefully would be proud of.

It would not have been possible for each of us on their own to come up with anything remotely interesting, tucked away into the dark corners of a dimly lit room. We struggled enough trying to communicate online and figuring out ways to create a scene from scratch which dealt with the subject matter. Long Zoom sessions, constant and extensive rewrites and a complete revamping of the scene were part of the process. Of course, that is how creative processes work, however, the frustration felt at some point seemed stronger sitting in front of a screen. But we didn't give up and came up with something we felt comfortable with.

We went through many different versions, and within weeks our scene changed from being comedic to being more tragic. It was hard to write without actually meeting up, hard to get creative when not sitting face to face, but once we had some ideas and rough sketches, the first fragment of dialogue, we were able to move on from there. Work on what had already been worked out by someone else. Comment and improve, sometimes discard, and sometimes write something completely new. I cannot imagine producing anything without the inexhaustible creativity and energy of my partners.

Together we made light of the situation, bounced ideas off each other and engaged with the subject matter. We decided against using just one early modern text as a reference for our project. We rather took Shakespeare's characters and planted them into a what if-scenario: "What if Shakespeare's characters were still alive, having to reenact their play and being affected by the changing nature, and someone having to look after it?" There are also many other texts from the period dealing with environmental issues worth looking into, such as, for example, Dekker and Middleton's News from Gravesend Sent to Nobody (1604) which reflects on the ‘necessity’ of the plague or Margaret Cavendish's poem A Dialogue Between an Oak and a Man Cutting Him Down (1653), which engages with deforestation.

Not Shakespeare, though, but Christopher Marlowe, who has been given the task and responsibility to handle the situation against his will, has to try to work it out. One man to figure out the problems of everyone else, which ultimately are also his own. But there are some things we just cannot do on our own. Some things are too big and require too much effort to try to achieve on your own. We cannot fix everyone's problems, and we certainly cannot regrow a forest all on our own. A communal problem needs a community to solve it. Therefore, Marlowe tries to go for the easy solution and get help. In order to regrow trees, he turns to a higher being, Oberon, to have them magically regrown. However, the magic is gone. Deforestation has drained the fairy king of his once held powers.

This seminar made it all the more clearer to me, how impossible it is to work alone. A theatre production requires a team for a reason. There are too many tasks, too many required skills, and too many things to keep track of, making it impossible for one person to handle everything on their own. And this seminar was no different. In trying to work through a complex topic like ecocriticism in the Early Modern Age in only three days, we split up into groups, each to work on a presentation and hosting a session on one particular enviromental issue. Similarly, when working on the individual performance projects, we split into groups once more to create parts which would then be assembled into a large project.

At first I was intrigued by the seminar and the mystery of how the two – in my opinion separate – fields of study, early modern literature and ecocriticism could be studied together. I was unaware of the environmental concerns in the period and how important they were for the culture of the time. Secondly, since a lot of friends took part in the course as well, and as I have a practical interest in theatre, it was clear to me that I had to take part. I was interested and enthusiastic about getting onto a stage with a group of nice people and performing something again after such a long time, deprived of any form of theatre experience due to the pandemic. I was optimistic, like probably many, that we would be able to actually perform in a theatre in front of an, albeit smaller, audience.

However, given the circumstances, we had to change our ideas and how we would meet in the seminar. And we did that together. We came up with possible solutions on how to carry out the theatre laboratory and how to make online performances possible. We discussed, imagined and worked together to create a performance we might not have imagined, but which we hopefully would be proud of.

It would not have been possible for each of us on their own to come up with anything remotely interesting, tucked away into the dark corners of a dimly lit room. We struggled enough trying to communicate online and figuring out ways to create a scene from scratch which dealt with the subject matter. Long Zoom sessions, constant and extensive rewrites and a complete revamping of the scene were part of the process. Of course, that is how creative processes work, however, the frustration felt at some point seemed stronger sitting in front of a screen. But we didn't give up and came up with something we felt comfortable with.

We went through many different versions, and within weeks our scene changed from being comedic to being more tragic. It was hard to write without actually meeting up, hard to get creative when not sitting face to face, but once we had some ideas and rough sketches, the first fragment of dialogue, we were able to move on from there. Work on what had already been worked out by someone else. Comment and improve, sometimes discard, and sometimes write something completely new. I cannot imagine producing anything without the inexhaustible creativity and energy of my partners.

Together we made light of the situation, bounced ideas off each other and engaged with the subject matter. We decided against using just one early modern text as a reference for our project. We rather took Shakespeare's characters and planted them into a what if-scenario: "What if Shakespeare's characters were still alive, having to reenact their play and being affected by the changing nature, and someone having to look after it?" There are also many other texts from the period dealing with environmental issues worth looking into, such as, for example, Dekker and Middleton's News from Gravesend Sent to Nobody (1604) which reflects on the ‘necessity’ of the plague or Margaret Cavendish's poem A Dialogue Between an Oak and a Man Cutting Him Down (1653), which engages with deforestation.

Wasteland, Baby!

a bricolage, borrowing characters from Shakespeare

by Anthea Ziermann (B.A. Student of English and Philosophy, M.A. Student of Theatre Studies)

There is an ancient belief that gods and other supernatural entities exist because we believe in them, that our thoughts possess the power to create. It dates back to Buddhist origins and has become immensely popular in contemporary literature, made famous by authors like Neil Gaiman (American Gods) or Terry Pratchett (Small Gods) and resonating with modern anthropocentric and atheist tendencies.

For our project we took the idea one step further, imagining what it would be like if this concept applied not only to gods, but to all man-made creatures and beings, including legendary and mythological figures like Odysseus, Gilgamesh, and King Arthur, as well as more modern fictional characters from novels and plays like, for example, by Shakespeare. What if, once these figures attain a certain popularity and are well remembered even four hundred years later (or more, considering how many characters in Shakespeare's works are borrowed from other sources), they become not only immortal, but tangible, present?

This being of course only a theoretical concept and not actually applicable to the 'real world', for a theatrical project we found it just fit. What would happen if Oberon and Titania, King and Queen of the faeries, were to live amongst humans and witness the decline of nature by the hands of the species that created them? How would Ariel, Prospero's air spirit, react to being asked for help by the same humans that created these environmental problems in the first place?

At first, we struggled. Everyone faces some sort of struggle currently, but for theatre businesses on a larger scale and smaller theatre projects like ours in a more personal context, the situation is even more difficult. Not only does our art heavily depend on the interaction between people, equally onstage and with the audience, the whole process of creating a theatre project is one of meeting and talking, trying and changing, and most of these aspects don't work as well while one is staring at video tiles on a computer screen. Creativity is a fragile and volatile good, and it is best kept in a group where there are others to catch it in case it breaks free.

We managed to produce some ideas, writing a first version of the scene which we then discarded completely. It turned out that the comical approach we had originally selected, partly to help ourselves cope with the unusual situation but also to generally liven things up, did not do justice to the seriousness of the overarching topic. In the first version, there were Shakespeare characters on screen, trying to come to terms with Zoom technology while sitting down to engage in environmental activism. Oberon, struggling with microphone settings. Puck fooling around in the background like a toddler or some agitated pet. Cut to Titania trying to be productive and work out her husband's problems at the same time. Comic reduction, and it worked – in a way. It was amusing. But that was about it.

Anne Carson, in her preface to Herakles, says that "Gods, to their eternal chagrin, are comic", and that is because of their immortality, their invulnerability. But what if they are not? The moment gods and godlike creatures become vulnerable, they acquire tragic potential. And what better way for Oberon and Titania, for Ariel and the Witches to go down than with the very material that shapes them? If Nature suffers, so do they.

The central idea our project revolves around is this: Humans are very good at exploiting, yet very bad at admitting to the damage they have done. In times of peace and prosperity, we pat ourselves on our backs. In times of need, we turn to our gods. Why have they forsaken us? What have we done to deserve being subjected to their whims and will?

I am not suggesting that Oberon and Titania are gods. Neither am I saying that Puck and Ariel, or the Witches from Macbeth, can in any way be compared to the deities that inspired actual (world) religions. What I am saying, though, is that as rulers of the fairies, elemental spirits, supernatural beings, and embodiments of Nature, or at least aspects of it, they have existed for a long time and represent the way we imagine our environment. Especially Oberon, whose name dates back to the 13th century and is derived from Alberich, meaning 'elf-king' in the Nibelungenlied, and Titania, who is mentioned in Ovid's Metamorphoses as a variant of Diana or Circe, have become part of our cultural memory. But no matter how many productions of the play that made them famous we put on, if we stop caring about Earth and Nature, they will eventually disappear.

This might be a bold thesis, but it is an honest one. With our project, we tried to raise questions about responsibility and how it is handled. The narrative frame in which Christopher Marlowe appears does not only serve the purpose of tying the individual scenes together by introducing a mediator between the individual parties, but also to show how easily responsibility is delegated to others, to put it nicely.

The almost humorous beginning about Malcolm refusing to march towards Dunsinane for the lack of trees to hide behind and Shakespeare being stressed about it quickly evolves into a display of Oberon's state of derangement and disarray, a direct consequence of the waning of woodland areas all over the world. In search for other powers that might help him concerning Malcolm and Oberon, Marlowe turns to other supernatural entities he knows. What was originally intended as a space for those characters to remind us that it is humanity's task to mend what they broke, quickly turned into an account of exhaustion and despair. It is not that the fairies, the spirits, and the witches don't want to help us, they simply lost their power to do so. In creating the problem we now ask them to fix, we stripped them of their essence and their magic.

This is, admittedly, a very fanciful approach to a serious topic, and although it has tragic qualities and, hopefully, some artistic value, it fails to produce any actual real world evidence for or relevance of what we are saying. We are aware of that. But admidst the fearsome and terrible news we get bombarded with everyday, it might prove interesting, if not useful, to tug more gently at one of the very core strings in the heart of humanity, and that is mythology. There is a reason important messages have been conveyed in similes and images and represented by allegorical figures since time immemorial. Over the course of this short scene collection, this is what we aim to do.

The ending, first aporetic and then slightly humorous, is not completely allegorical, though. Plant a tree if you can. Get your hands into the dirt and feel what it is that gives us life and to which we give so little back. But most importantly, never stop investigating and asking questions, even if it means some work for you in the end.

For our project we took the idea one step further, imagining what it would be like if this concept applied not only to gods, but to all man-made creatures and beings, including legendary and mythological figures like Odysseus, Gilgamesh, and King Arthur, as well as more modern fictional characters from novels and plays like, for example, by Shakespeare. What if, once these figures attain a certain popularity and are well remembered even four hundred years later (or more, considering how many characters in Shakespeare's works are borrowed from other sources), they become not only immortal, but tangible, present?

This being of course only a theoretical concept and not actually applicable to the 'real world', for a theatrical project we found it just fit. What would happen if Oberon and Titania, King and Queen of the faeries, were to live amongst humans and witness the decline of nature by the hands of the species that created them? How would Ariel, Prospero's air spirit, react to being asked for help by the same humans that created these environmental problems in the first place?

At first, we struggled. Everyone faces some sort of struggle currently, but for theatre businesses on a larger scale and smaller theatre projects like ours in a more personal context, the situation is even more difficult. Not only does our art heavily depend on the interaction between people, equally onstage and with the audience, the whole process of creating a theatre project is one of meeting and talking, trying and changing, and most of these aspects don't work as well while one is staring at video tiles on a computer screen. Creativity is a fragile and volatile good, and it is best kept in a group where there are others to catch it in case it breaks free.

We managed to produce some ideas, writing a first version of the scene which we then discarded completely. It turned out that the comical approach we had originally selected, partly to help ourselves cope with the unusual situation but also to generally liven things up, did not do justice to the seriousness of the overarching topic. In the first version, there were Shakespeare characters on screen, trying to come to terms with Zoom technology while sitting down to engage in environmental activism. Oberon, struggling with microphone settings. Puck fooling around in the background like a toddler or some agitated pet. Cut to Titania trying to be productive and work out her husband's problems at the same time. Comic reduction, and it worked – in a way. It was amusing. But that was about it.

Anne Carson, in her preface to Herakles, says that "Gods, to their eternal chagrin, are comic", and that is because of their immortality, their invulnerability. But what if they are not? The moment gods and godlike creatures become vulnerable, they acquire tragic potential. And what better way for Oberon and Titania, for Ariel and the Witches to go down than with the very material that shapes them? If Nature suffers, so do they.

The central idea our project revolves around is this: Humans are very good at exploiting, yet very bad at admitting to the damage they have done. In times of peace and prosperity, we pat ourselves on our backs. In times of need, we turn to our gods. Why have they forsaken us? What have we done to deserve being subjected to their whims and will?

I am not suggesting that Oberon and Titania are gods. Neither am I saying that Puck and Ariel, or the Witches from Macbeth, can in any way be compared to the deities that inspired actual (world) religions. What I am saying, though, is that as rulers of the fairies, elemental spirits, supernatural beings, and embodiments of Nature, or at least aspects of it, they have existed for a long time and represent the way we imagine our environment. Especially Oberon, whose name dates back to the 13th century and is derived from Alberich, meaning 'elf-king' in the Nibelungenlied, and Titania, who is mentioned in Ovid's Metamorphoses as a variant of Diana or Circe, have become part of our cultural memory. But no matter how many productions of the play that made them famous we put on, if we stop caring about Earth and Nature, they will eventually disappear.

This might be a bold thesis, but it is an honest one. With our project, we tried to raise questions about responsibility and how it is handled. The narrative frame in which Christopher Marlowe appears does not only serve the purpose of tying the individual scenes together by introducing a mediator between the individual parties, but also to show how easily responsibility is delegated to others, to put it nicely.

The almost humorous beginning about Malcolm refusing to march towards Dunsinane for the lack of trees to hide behind and Shakespeare being stressed about it quickly evolves into a display of Oberon's state of derangement and disarray, a direct consequence of the waning of woodland areas all over the world. In search for other powers that might help him concerning Malcolm and Oberon, Marlowe turns to other supernatural entities he knows. What was originally intended as a space for those characters to remind us that it is humanity's task to mend what they broke, quickly turned into an account of exhaustion and despair. It is not that the fairies, the spirits, and the witches don't want to help us, they simply lost their power to do so. In creating the problem we now ask them to fix, we stripped them of their essence and their magic.

This is, admittedly, a very fanciful approach to a serious topic, and although it has tragic qualities and, hopefully, some artistic value, it fails to produce any actual real world evidence for or relevance of what we are saying. We are aware of that. But admidst the fearsome and terrible news we get bombarded with everyday, it might prove interesting, if not useful, to tug more gently at one of the very core strings in the heart of humanity, and that is mythology. There is a reason important messages have been conveyed in similes and images and represented by allegorical figures since time immemorial. Over the course of this short scene collection, this is what we aim to do.

The ending, first aporetic and then slightly humorous, is not completely allegorical, though. Plant a tree if you can. Get your hands into the dirt and feel what it is that gives us life and to which we give so little back. But most importantly, never stop investigating and asking questions, even if it means some work for you in the end.

Texts used:

- Carson, Anne. Grief Lesson. Four Plays by Euripides. 2006. NYRB Classics, 2008.

- Griffin Stokes, Francis. Who's Who in Shakespeare. 1924. Bracken Books, 1989.

- Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night's Dream. Ca. 1594.

- ---. Macbeth. Ca. 1606.

- ---. The Tempest. Ca. 1611.